In the last couple of days left until the end of the summer, stocks seemed to shake off their August pessimism. The Nasdaq Composite (NDAQ) surged over 6% from its August low, cutting the monthly loss from 7.3% to just 1.7%. The same pattern was in place for the main U.S. indexes. Stocks seem to be welcoming September with a fresh amount of hope; but is it justified?

“Sell in August and Go Away” Doesn’t Rhyme

As usual, at the end of August, investors begin to discuss the “September Effect,” a phenomenon of historically low stock market returns seen during the month. Mind you, this isn’t another one of the stock market myths: there’s actually a solid statistical base, dating back nearly a century.

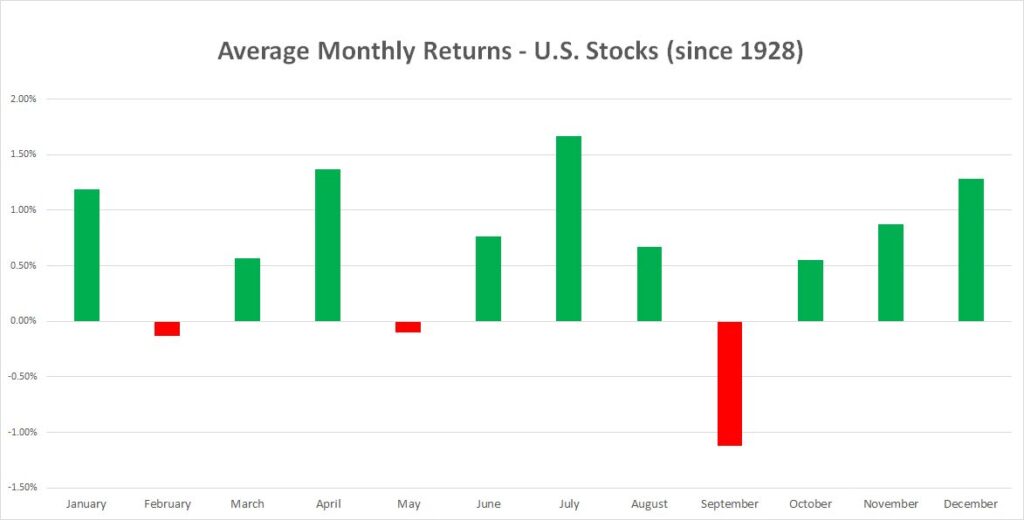

September is the worst month for stocks; this has been registered over the past 100 years as well as over shorter time spans. According to Dow Jones data, U.S. stocks have, on average, shed 1.12% in September, based on data from 1928.

Some of this poor performance can be explained by a few outsized monthly losses, of course (like September 1931, the worst month of the Great Depression). But that’s not the whole story, as September is also the only month that has seen stocks rise in fewer than half the years in the past century.

Data: Dow Jones

Looking at a more modern history, say, since 1990, the average S&P 500 (SPX) decline for the month decreases to 0.8%, but the observed negative eventuality remains in place. It has stayed unchanged even in the pre-election years, in which stocks usually do much better than in regular times.

The statistics hold for all major indexes. Thus, September is the only month in the history of the Nasdaq Composite, dating back to 1971, with a negative average return. Moreover, the September Effect is not solely a U.S. phenomenon, as records show similar stock behavior in other markets, as well. According to eToro market research, the average September return for 15 main global indexes (including SPX, TSX, DAX, CAC, FTSE-250, and others) in the past 50 years, was minus 1.1%.

Some observers say that the September Effect has become muted in recent times. Well, yes, in the past 20 years (2002-2022), September brought negative SPX returns on ten occasions, that is, in just half the times. But in the past decade, the S&P 500 was in the red six times, i.e., in 60% of years, confirming the long-term statistics.

Are we doomed to suffer September losses? And who or what is to blame?

Looking at a more modern history, say, since 1990, the average S&P 500 (SPX) decline for the month decreases to 0.8%, but the observed negative eventuality remains in place. It has stayed unchanged even in the pre-election years, in which stocks usually do much better than in regular times.

Blaming Humans for Being Human

Investors, economists, psychologists, and laymen have supplied about as many explanations for the September Effect as there are clouds in the sky in September.

Some theories say that what causes the effect is the rebalancing by large mutual funds, whose fiscal year ends in September. The fund managers dump losing positions to reduce the amount of taxes they must pay (and to look better in their investor presentations). But, according to JPMorgan (JPM), funds with fiscal year-end in September command much smaller assets than their December year-ending peers, so their actions have a lesser effect on the markets.

Another hypothesis, stemming from human psychology, blames the self-fulfilling prophecy phenomenon. As investors read about the “September Effect” in the media, they don’t want to take any chances with the statistics, and thus cash out. This theory looks plausible at first, but if it were true, the markets would fall every September, which is, thankfully, not the case.

Some explanations blame summer holidays and, again, psychology. When investors return from their August vacations and get back behind their desks, without a sunny beach to look forward to anymore and with the winter melancholy creeping in, they may be prone to see things in a more negative light. Suddenly, all those minor economic, financial, or market clouds that were easy to shrug off in the warm summer light, begin to look like an impending storm, demanding immediate action (selling). However, data shows that most vacation-related selling is done before the vacation, not after.

There is one piece of research from Cambridge University, dating back to 2017, that found evidence of seasonality in investor risk aversion trends, affecting their choice of mutual funds. Simply put, investors tend to prefer riskier funds in spring and safer bets in fall. So, there may be something going on with the investor psychology and the September Effect, but none of it explains why stocks do so well in November, December, and January.

In short, the September Effect remains an unexplainable statistical quirk. Actually, market participants should be grateful for the absence of an explanation that holds water. If ever there is one, everyone would try to outrun everyone else and sell earlier than others, and that could be the end of the stock markets.

Is This Time Different?

September-fearing investors can find some hope in the fact that October is a positive-outcome month, according to statistics. That’s true even though it is the most volatile month for stocks, on average, with more frequent large swings in stock prices than in any other month. On a more optimistic note, the same statistics say that many of the rallies and even bull markets began in October, setting the scene for November and December, which are historically among the best months for stocks.

The problem is that while statistics looks at averages of large sets of data, we are living through one episode each time, which can be vastly different from its predecessors. Thus, with all else held equal, a meaningful rally usually needs lower-than-average valuations to ignite.

Stocks have seen a huge rally this year, with the NDAQ up 35% and the Nasdaq-100 (NDX) up over 42% year-to-date, despite the negative news hitting from all directions. The increases are of a comparable magnitude, but, interestingly, the valuations are not the same. While the broad tech index’s price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 23.4 is lower than its 10-year and 5-year averages, the NDX is seriously overvalued at a P/E of 31.8 (versus the historical average of 25).

Blame the outsized melt-up in the shares of Nvidia (NVDA), as well as a year-to-date surge of Apple (AAPL), Meta (META), and other tech mega-caps, who make up more than half of its weight. Still, on average, the markets are quite pricey, while far from the bubble territory (apart from individual stocks). Of course, low valuations don’t mean that the rally is around the corner, and higher-than-average stock prices don’t predict a crash. But inflated valuations can significantly worsen the drop, if and when it happens.

Correlation Is Not Causation

So, what should a rational investor do, entering a statistically weak September, and anticipating a statistically volatile October? Wouldn’t it be prudent to wait out the dog days outside of the markets and reenter into the statistically expected rally in November?

Not so fast. Yes, buying into the overvalued Nasdaq-100 now doesn’t seem to be a great idea. But it doesn’t mean that investors should pass on an opportunity to buy fundamentally sound companies at a reasonable price, let alone sell stocks they already hold.

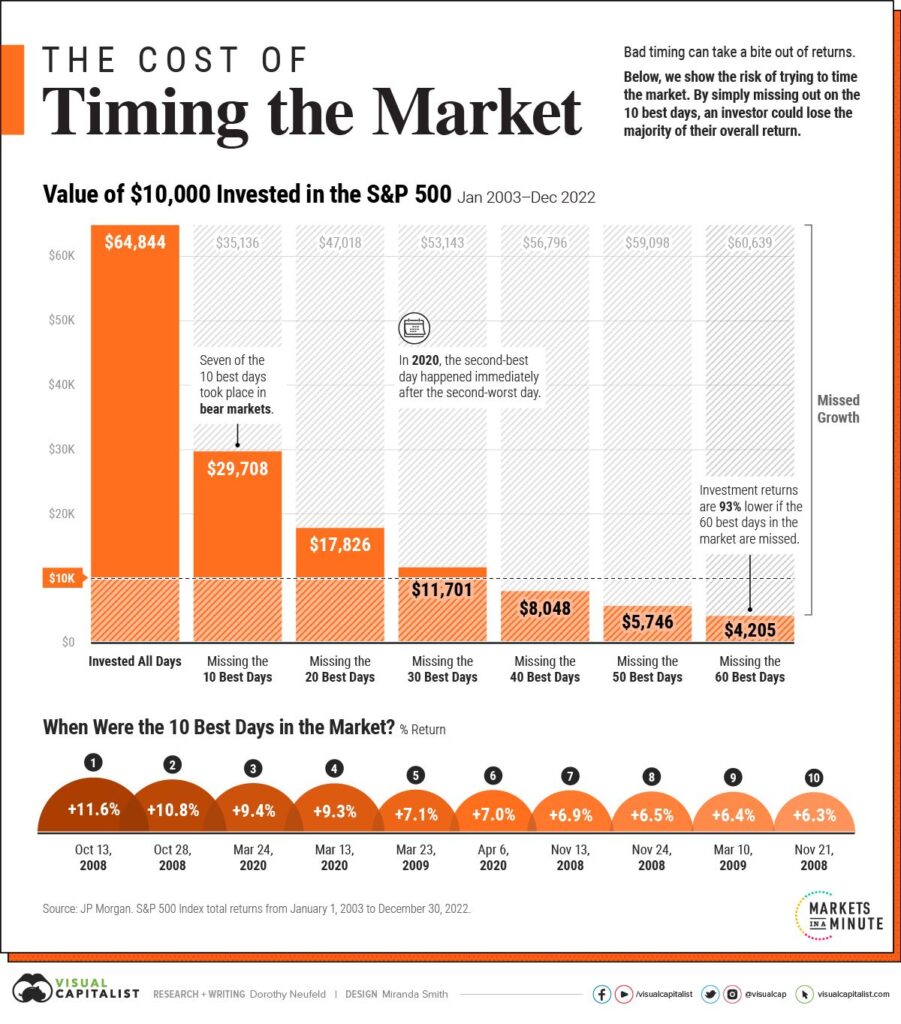

Statistically (again!), there have been many great Septembers, Octobers, and Junes. Since we can’t really predict the September Effect or any other market behavior, we should be extremely careful not to miss out on potential gains, which could thwart long-term returns. According to data, investors who have missed just ten best days during the past 20 years, have their return for that period slashed by 55%. Those who missed the 60 best days in the markets received only 7% of the return of investors who have stayed put.

Source: Visual Capitalist

So, the conclusion is clear: buy fundamentally strong companies at reasonable prices; don’t buy on hype and sell on rumors; stay invested – and, of course, don’t base your investing decisions on any meaningless correlation, however statistically correct it seems.

Questions or Comments about the article? Write to editor@tipranks.com