The regional banking crisis of March 2023 continues to weigh on investor sentiment toward bank stocks even now, half a year later. However, discerning investors have noticed that some banks were much better off than others during and in the aftermath of the crisis. Now these investors are wondering whether the drop in bank shares has created a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pick up some high-quality banking stocks at a steep discount and capitalize on the crisis – or whether there are more dangers ahead.

Bank Stocks Still in Crisis Mode

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 was a life-changing, paradigm-shifting, traumatic event for investors. It had such a profound impact on investors’ psyche, that we now tend to use it as a reference point for any event even remotely reminding us of a financial crisis.

That is why the collapse of a small, by no means systemically important regional bank, sparked a panic reaction back in March, leading to the contagious spread of fears and the downfall of several other regional or niche institutions. U.S. regulators took extremely wide and decisive steps to limit the contagion, and “with a little help from a friend,” aka JPMorgan (JPM) and other prominent banking behemoths, the crisis was over and done with.

But was it, really? Judging by investor sentiment, it is not entirely over yet.

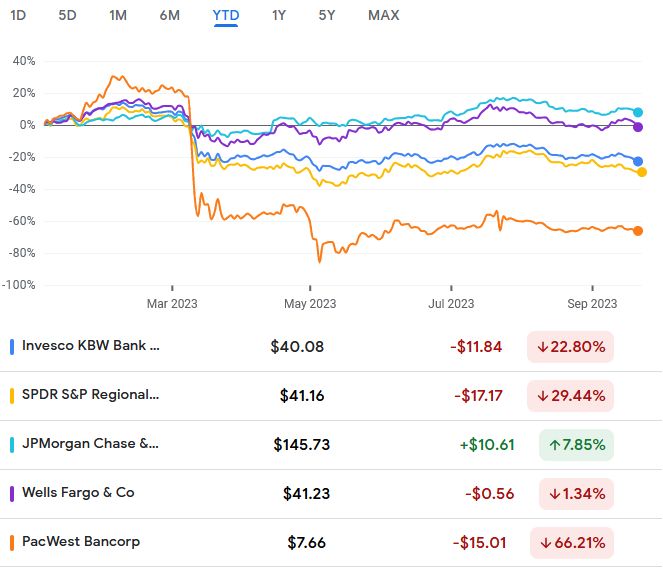

The Invesco KBW Bank ETF (KBWB), which puts the biggest emphasis on the stocks of giant money-center banks like Goldman Sachs (GS), Wells Fargo (WFC), Morgan Stanley (MS), JPMorgan Chase, and Bank of America (BAC), but also holds several of the largest regional banks, is down 23% year-to-date.

Even among the largest financial institutions, stock performance differs widely. While Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Citigroup (C) are still in the red for the year so far, some other banking giant stocks have rebounded. But the regional banks are still way below the zero threshold for the year. Even the large, “super-regional” PNC Financial Services Group (PNC) is still at a loss of over 24%; most of the smaller banks are much worse off. First Horizon (FHN) is down 55% year-to-date, KeyCorp (KEY) has lost 40%, and Truist Financial (TFC) has dropped 36%.

Source: Google Finance

The distrust towards the banks in general is reflected in the investor fund flows. Although KBWB is now net positive in terms of inflows for the past six months (since the banking crisis began), the total is widely skewed by a two-week surge that took place back in July, when investor sentiment was strongly spurred by speculations of a Goldilocks economic scenario, with hopes for a decline in inflation without a recession. Later, in August, the market mood soured again, as worries about the health of the banking sector resurfaced.

The SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (KRE), which holds only regional and smaller banks, has seen investor outflows of nearly $1 billion in the past six months. The ETF is down 30% year-to-date, with some of its holdings, such as PacWest Bancorp (PACW), still saddled with huge losses for the year.

The Fed’s Heavy Hand

Since March 2022, the Federal Reserve has engaged in a “fast and furious” rate hiking campaign to combat inflation. At first, banks were expected to mostly benefit from the increasing interest rates, as those help them earn a wider spread between what they pay to depositors and what they earn on loans. However, when fears of a recession arose, bank stocks felt the pain. Recessions are very harmful to the banks, as they hit the financial sector’s earnings through delinquencies and lower credit and loan demand.

While March’s bank crisis wasn’t caused by a decline in economic activity, it was a direct result of the Fed’s hiking campaign. The sharp rise in interest rates, coupled with a sudden funding drought and rising opportunities for higher income than the interest paid by banks, led to a surge in deposit withdrawals, mostly hitting smaller banks that don’t engage in investment and underwriting businesses.

The rising rates also depressed the prices of banks’ bond holdings; losses on the books forced them to raise capital, spooking clients and investors alike. These unrealized losses on the banks’ books amounted to $0.5 trillion at the end of March, raising concerns about the health of the financial system and its ability to support economic activity through lending and investing.

Regional and smaller banks are responsible for about 70% of small business lending and for approximately 80% of real estate lending. Thus, they are much more susceptible to economic downturns – and, at the same time, trouble in their ranks spells trouble for the economy.

Is The Banking Crisis Over?

As a result of the feared crisis contagion, billions of dollars of deposits flew from regional and smaller banks to the likes of Citibank and Bank of America. These giants’ balance books remained healthy thanks to the strict regulations and oversight, in place since the GFC, for the institutions deemed “too big to fail.” These financial stalwarts largely benefitted from the crisis, as Americans moved hundreds of billions of dollars from the regional and smaller banks into their deposits. Some, like JPMorgan, had an opportunity to scoop up assets of their failing smaller peers for a few cents on a dollar.

However, large banks weren’t totally left unscathed. As the skies cleared after the panic, they, too, saw their deposit base shrink, as consumers went on a spending spree or moved to higher-yielding alternatives, such as Treasuries or money-market funds. Their stocks mostly haven’t recovered yet from the huge blow dealt to the whole industry by the “March madness.”

But regional and smaller banks are still reeling from the crisis. They now have to pay much higher interest on deposits to compensate for the perceived risk and to be able to compete with other savings instruments. They also have to tighten lending standards to try and decrease their exposure to economic risks at a time when the demand for loans is falling, while credit quality is decreasing across the board. Smaller banks’ fundamentals are still questionable, given this disposition.

Meanwhile, analysts slashed their 2023 EPS forecast for KRE-held regional and smaller banks by 40%, according to FactSet, and that doesn’t account for a swath of negative macro outcomes that could still materialize.

Property Pain, No One’s Gain

Fears of a recession in the U.S. are resurfacing, with many analysts and economists saying that the pandemic-era corporate and personal savings helped merely push it down the road, not avoid it. If that is the case, the high-interest rates will hit consumer demand and depress loan demand even more. At the same time, mounting consumer debt, particularly credit card debt, can be expected to sour at much higher rates during the economic downturn, leading to wider charge-offs and losses.

Another pain point for the smaller banks is their high exposure to commercial real estate (CRE) loans. These loans, which are risky even in a good economy, now spell trouble due to lower demand, falling property values, and the scarcity of funding, which can lead to additional loan losses for the banks. According to a global rating agency Fitch Ratings, about 35% of the CRE loans maturing until the end of this year will not be able to refinance; how much of these will be written down as losses remains to be seen.

The credit rating agency Moody’s downgraded ten small- to mid-sized banks, citing various economic and financial strains, and putting a specific emphasis on risks associated with their CRE exposure. The agency also placed several lenders under review for possible downgrades. S&P Global Ratings quickly followed suit, downgrading five banks it deemed less resilient than their peers and placing some more lenders under review.

Fitch downgraded the whole U.S. banking operating environment back in June; one more notch down – and all U.S. banks, including the best of them, will be downgraded. Rating downgrades increase the cost of funding, hitting the bottom lines. They also weigh on sentiment, pressing down the stocks of the banks deemed riskier than investors previously believed.

Don’t Buy the House Without Checking the Plumbing

So, does all that mean that banks are poor investments? Certainly not.

For more risk-inclined investors, the banking stocks’ underperformance can present a great opportunity to gain exposure at a very low cost. However, a great deal of discernment is needed to avoid value traps or outright losses on investment.

First of all, now is not a great time to buy a bank-stock ETF, since these funds passively follow indexes without analyzing the holdings or managing exposure in accordance with the economic and market conditions (that’s why they are so cheap). As a result, their holdings include great and profitable banks along with those that could be next to be shut and sold if something goes wrong. What that can do to investor sentiment is reflected in the difference in performances of the KBWB ETF and the specific quality bank stocks it holds among others.

In addition, investing in regional and smaller banks doesn’t seem to be a very good idea at the moment, as the economic outlook is still highly uncertain, and the risks are clearly tilted to the downside. True, some of the larger regional banks may project a picture of perfect health, but it’s hard to be positive about their future without looking deep into their loan books and balance sheets – an analysis that may be too demanding for an individual investor.

To note, one of the banks downgraded by Moody’s is the M&T Bank (MTB), the 19th largest U.S. bank by assets, while one of the banks placed under review for a possible downgrade is the Bank of New York Mellon (BK), the 11th largest bank in the country. This means that the dangers may be lurking even behind a magnificent façade.

Some Banks Are Very Investable

Meanwhile, large, systemically important money-center banks are not expected to go bust, even in times of a hard recession. They may see some write-offs, as well as a decline in loans and deposits, and, of course, their stocks can experience volatility and losses. However, longer term, they are as safe as houses (well, much safer). After the GFC, major regulation changes reduced their risk by increasing capital requirements and decreasing leverage, while the Federal Reserve’s “stress testing” provided another level of assurance. The same regulatory changes are probably coming to smaller banks, as well, but they are not in place yet. In addition, larger banks make money from investing, underwriting, and other lucrative venues, which increases their profitability and can counterweigh commercial banking headwinds.

Of course, even when the stock valuations at purchase are very low, investors shouldn’t expect large banks’ stocks to outperform the broad market in the long term, even though some of them have shown outstanding performance in recent years. Their main selling points are confidence, diversification, and dividends.

Yes, JPMorgan’s and Goldman Sachs’s shares surely can fall, but, since we know that these institutions will not go bankrupt, we can hold their stocks with confidence that they will rebound. Besides, bank stocks can provide a great diversifier for a long-term investment portfolio, cushioning it against volatility in other sectors in different economic scenarios. But the most enticing for long-term investors is the feature of high dividend yields, typical for financial sector stocks.

JPMorgan pays a 2.7% dividend yield, Goldman Sachs – 2.8%, Wells Fargo – 2.9%, Bank of America – 3.2%, Morgan Stanley – 3.6%, and Citigroup shells out a yield of 4.8%. These venerable institutions have been paying and increasing dividends for many years and are expected to continue doing so for years to come. So, while current circumstances don’t provide an easy field for short-term investment in bank stocks, aspiring long-term income investors may want to take a look at shares of these banking giants.